It’s the season of high-speed wind, freak snowstorms and inconceivably large hailstones, which means that I, for one, have spent a large portion of the month inside, reading. A redeeming factor in March’s favor is that Kelly Link has a new book out, and it doesn’t disappoint.

White Cat, Black Dog (March 2, Penguin Random House), is a collection of reimagined fairy tales that draw inspiration from the stories of the Brothers Grimm, 17th-century French lore and Scottish ballads. But even with its roots in these age-old tales, Link’s stories are inextricably entwined with the anxieties, hopes and longings of the modern world.

Link is the author of the story collections Stranger Things Happen, Magic for Beginners, Pretty Monsters and Get in Trouble. She’s also a 2018 MacArthur Fellow, co-founder of Small Beer Press and co-editor of the occasional zine, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet (which, if you haven’t checked out already, I’d recommend you do post-haste).

Which is all to say Link knows precisely what she’s doing. The first story in White Cat, Black Dog, “The White Cat’s Divorce,” reads like Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy was a writer on HBO’s Succession. Based on Countess d’Aulnoy’s literary fairy tale, “La Chatte Blanche,” “The White Cat’s Divorce” is the story of a rich man who sets his three sons a series of improbable tasks, ostensibly with a view to choosing an heir, but really in an effort to stave off his own mortality. He has begun to dream he has a fourth child whose name is Death, and the sight of his three adult sons becomes a memento mori. To get them out from underfoot, he asks them to spend a year searching for the smallest, most wonderful dog to be his companion. The youngest son sets off in a cherry red roadster and makes his way to Colorado, where he encounters a community of cat-people budgrowers who help him with his quest. The tale continues in this vein, an alloy of biting observational humor and a plot combining the fantastical and real in a way that makes the reader question the bounds of their own reality.

“The White Cat’s Divorce” sets the tone for the rest of the collection, which leads us through the stories of a man named Prince Hat who is promised to Hell, a troupe of entertainers whose world draws close to a lurking road where monsters walk and a woman who comes to understand fear in an airplane bathroom (understandable). The stories are exquisitely preposterous and continue down Link’s road of magical realism via death-defying billionaires and canceled Delta flights.

If I had to give these stories an overarching theme, it would be in how they exist so close to the taut line of apocalypse, which sings through the tales like a plucked string. Some hit just-this-side of it: “The Girl Who Did Not Know Fear,” “The Lady and the Fox.” Some exist just on the other side: “The White Road,” “The Game of Smash and Recovery.” But they all feel pulled inescapably, magnetically toward the end of days in a way that is uncomfortably familiar.

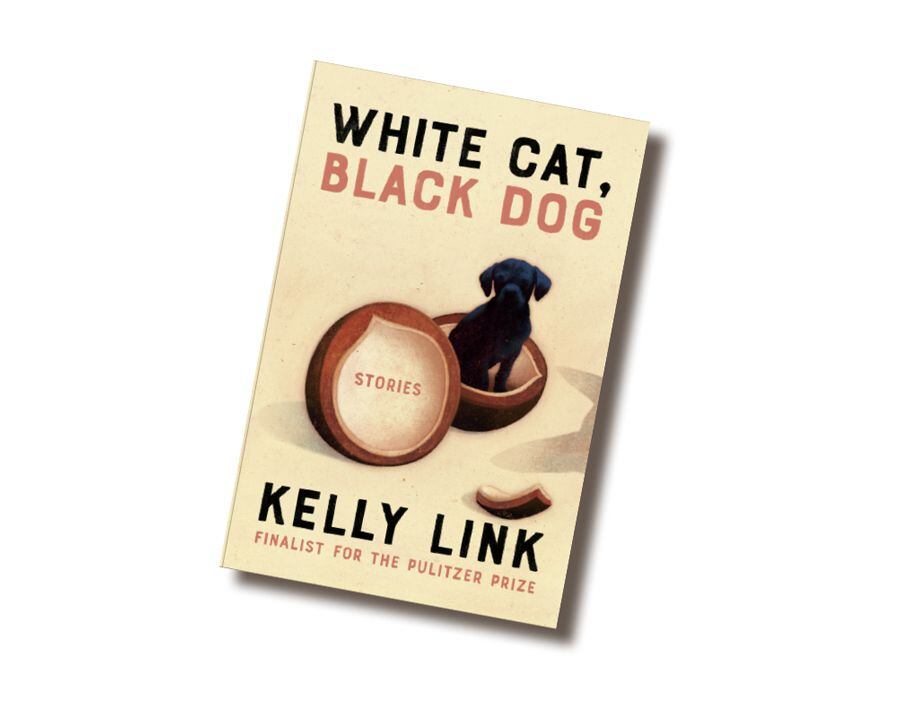

Writer Kelly Link’s new compendium of stories is a real doozy. (Sharona Jacobs Photography/)

There is also a grief and poignancy that flows through many of Link’s tales related to the climate crisis. It’s subtly but effectively wrought in “The Lady and the Fox,” a reimagining of the legendary Scottish ballad Tam Lin, and maybe my favorite of them all. The protagonist, Miranda, sees a mysterious man on Christmas day outside the home of family friends. The man returns each year on Christmas, but only when it snows. Each year as she anticipates his visit, she worries that this will be the year it won’t snow. Each year grows warmer.

Link’s stories deal with many of the same anxieties that underlie their forebears: the fear of, and fascination with, the unknown. But Link’s unknown differs in scale, spanning time, galaxies and the ever-expanding reach of human power. Her characters are drawn to this dimension, an impulse that leads both them and her readers through other worlds: worlds where dogs are born from the shell of a Macadamia nut, worlds where corpses keep death at bay for the living, worlds that contain portals to Hell: but Hell isn’t what we thought it would be. Maybe we were there all along.