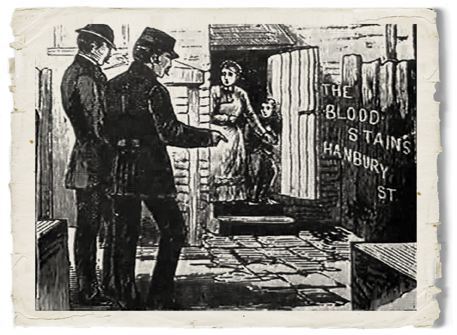

I can almost feel the panic, over a century later, felt by those who responded to the murder on that Saturday morning, 6 September, 1888 . The sad back yard of the run down tenement on Hanbury Street was separated by less than a half mile and just a week from the dark lonely murder scene on Buck's Row. And it seemed obvious the same maniac had been responsible for both horrors. After the murder of Martha Tabrem, the newspapers had called for more lighting around private residences. And after Polly Nichols' murder the Coroner's jury and the newspapers had both called for more gas lights in the dark public corners of Whitechapel. But this poor woman, who ever she was, had been murdered and butchered in the full light of morning. Logic seemed to offer no solution for this horror.

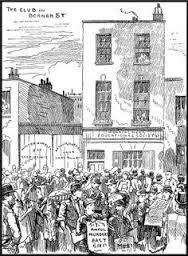

Like a blood stain soaking into the victim's worn clothing, the horror born in one man's tortured soul, was now being sucked up by every civilian gawker, uniformed constable and plain clothes detective in the Whitechapel division. It began to touch Inspector Joseph Luniss Chandler before six that morning as he watched two men running up Hanbury Street from the window of the Commercial Street Station (above) , and he felt the first faint sick feeling of what might be coming. He was the officer who responded at 6:02 am, to the men's report. Accompanied by several constables, Chandler arrived at 29 Hanbury to discover a crowd already jamming the narrow hallway. He ordered the hall cleared, sent an officer back to Commercial Street to fetch the ambulance cart and reinforcements, and another officer to cover the body with cloth bags, and dispatched yet another constable to fetch Dr George Bagster Phillips, the Divisional Police Surgeon.

Over his 20 year career as a doctor, the modest Dr. Phillips had developed a "a brusque, quick manner", and a self assurance in his own judgement. He stepped into the yard at about 6:20 that morning. Removing the covering bags, he noted the woman's “...left arm was placed across the left breast. The legs were drawn up, the feet resting on the ground, and the knees turned outwards.” The victim's face was swollen and bruised, and turned toward the fence. The tip of her swollen tongue was between her teeth, which seemed intact. But below the waist, “The body was terribly mutilated...”

He noted, "the body was cold except that there was a certain heat, under the intestines", but he took no temperatures. He added, "Stiffness of the limbs was not marked, but it was commencing…the blood had mainly flowed from the neck, which was well clotted. Dr. Phillips estimated the time of death to have occurred at least 2 or 3 hours earlier, or between 3:30 and 4:30 am. The doctor observed a handkerchief tied around the dead woman's throat. But below the cloth were two deep slashes, “...jagged and...right round the neck” On the fence next to the body he noticed what might be smears of blood. He thought the weapon which had created all the injuries might have been “a very sharp knife with a thin narrow blade...at least 6 to 8 inches in length”, perhaps a bayonet, a doctor's knife, or the kind of knife used in a slaughter house or by a butcher. But Doctor Phillips saw no evidence of a struggle in the yard, and he was certain the dead woman had come into the back yard under her own power.

At her feet, and between her legs, Dr. Phillips (above) saw a piece of muslin cloth, on which were an envelope corner, which had evidently been folded and used to carry 2 pills lying next to the paper. Next to them was a comb, still wrapped in paper. It occurred to Phillips the items had been placed there rather carefully, “that is to say, arranged there.” He also noticed a leather apron laying on the ground near a water faucet projecting from the rooming house wall. Inspector Chandler noted the items and collected them.

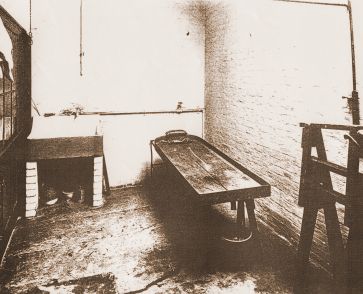

As soon as the ambulance cart (above) arrived, Dr. Phillips ordered the body be removed. The Bobbys lifted the mutilated corpse into a wicker coffin, which they used to carry the dead woman through the hall, out onto Hanbury Street. The doctor walked with the Bobbys pushing the ambulance cart to Brick Lane, then across to Montague Street, before turning east, followed by a crowd growing in numbers and agitation. They arrived at the Eagle street entrance to the Montague Street Mortuary a few moments before 7:00 am.

The gates locked the crowd outside (above), while the party waited for Robert Mann to unlock the shed. Once the body had been transferred to the examination table, Dr. Phillips issued specific instructions to the chastised attendant, Mr. Mann, that this body was not to be touched until he – the doctor - had returned to preform the autopsy. A few moments later, Inspector Chandler arrived, and issued identical instructions to Mann. Leaving Constable Barnes to keep an eye on the crowd at the Eagle Street gate, Dr. Phillips headed to the London Hospital to see patients, while Inspector Chandler returned to the Commercial Street station to begin preparing his investigation.

None of the warnings did any good, of course. Within two hours a lowly clerk at the Whitechapel Workhouse had dispatched two guardians (nurses' assistants) to the mortuary to wash all evidence off the body. Neither the staff nor population of the Work House understood that the offense in handling the corpse of Polly Nichols had not been that men had washed a woman's body, but that the body had been washed at all. But nowhere does it seem that any one bothered to explain that to them.

The London Daily News did its best to make up for not having a Sunday edition to report the murder and sell papers. Their report, on Monday, 10 September began, “On Saturday one more crime was added to the ghastly series of Whitechapel murders. Just before six that morning a woman was found murdered and mutilated at a lodging house in Hanbury street...The head...had been nearly severed from her body by one stroke of a sharp knife, and her mangled remains had been disposed about her in a way that suggested a delight in the slaughter for the slaughter's sake....inflicted nameless indignities on the dead body, indignity upon indignity, horror upon horror, and got clean away. The house teemed with life; it was near the hour of rising...yet no human being heard a cry or an alarm. The swiftness of it, the perfect mystery of it, are heightening effects of terror. The wildest imagination has never combined in fiction so many daring improbabilities as have here been accomplished in fact.”

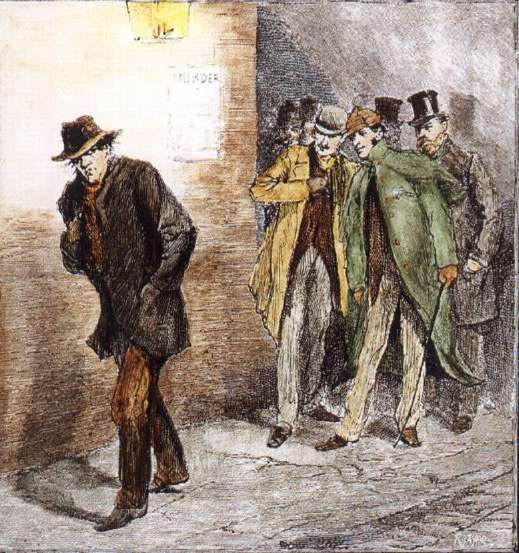

That same day The Daily Telegraph reported, “Mrs. Fiddymont, wife of the proprietor of the Prince Albert public-house...half a mile from the scene of the murder, states that at seven o'clock yesterday morning...there came into...a man whose rough appearance frightened her. He had on a brown stiff hat, a dark coat, and no waistcoat...he asked for "half a pint of four ale."....there were blood-spots on the back of his right hand...his shirt was torn. As soon as he had drunk the ale, which he swallowed at a gulp, he went out... she slipped out the other door, and watched him as he went towards Bishopsgate-street...” The wild eyed mystery man was last seen heading for Halfmoon street.

The Telegraph then added, “A number of sensational stories are altogether without corroboration, such, for instance, as the tale that writing was seen on the wall of No. 29: "I have now done three, and intend to do nine more and give myself up." One version says some such threat as "Five - Fifteen more and I give myself up," was written upon a piece of paper that was picked up. There has also been a good deal said about "Leather Apron”,.....So much has been said of "Leather Apron" that, when it became known that a leather apron had been discovered in the yard, the people immediately associated it with the supposed culprit. There were three aprons, in fact, and they belonged to workmen, who have no connection with the case.”

The East End News described the murders as, “...so distinctly outside the ordinary range of human experience that it has created a kind of stupor extending far beyond the district where the murders were committed...” The paper then added, “So many stories of "suspicious" incidents have cropped up since the murder, some of them evidently spontaneously generated by frantic terror, and... pointing in contrary directions, that....If the perpetrator...is not speedily brought to justice, it will be not only humiliating, but also an intolerable perpetuation of the danger.” The people of Whitechapel were beginning to see Leather Aprons on every street corner,

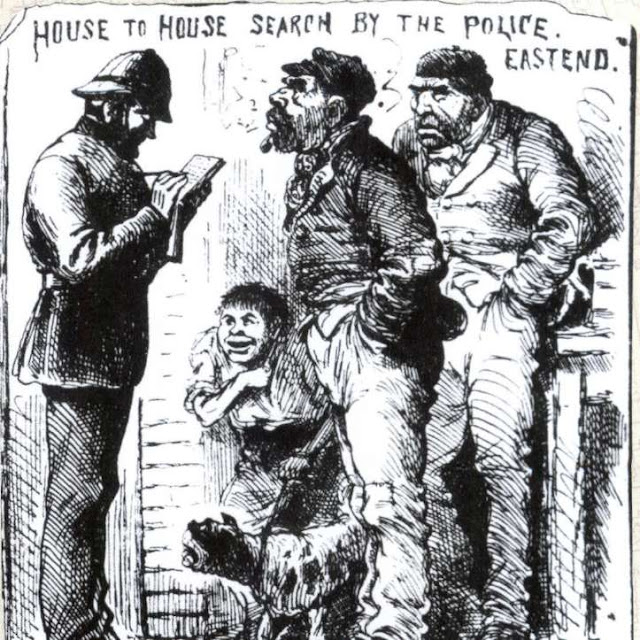

The London Evening News reported a conversation between “workmen” that seemed to hint at revolution brewing behind the slaughter. “But I want to know what the police is about?" This was met with the sneering observation of a companion, "Well, you must be a fool to ask a question of that sort. Why, the 'perlice' is too busy looking arter the changing of bus hosses in the West-end, and a-watchin' o' Trafalgar Square, to care what becomes of poor devils like us." The murmurs of approval which greeted this homely satire showed that the feeling towards the guardians of the peace is one of distrust...”.

The crimes were so horrible, the Daily Telegraph was eager for speculation, “It is a positive relief”, they wrote, “to escape from the fact to the theory of the crime.... No person could murder at these risks, and for these gains, with any sense of purpose in his acts as purpose is known to the sane. A monster is abroad. The murders defy all rules of motive...There was no more waste of effort than there is in the killing of a sheep. There could have been no more pity, or anger, or violent passion of any sort. The police have to find for us one of the most extraordinary monsters known to the history of mental and spiritual disease, a monster whose skull will have to be cast for all the surgical museums of the world. No other theory is admissible.”

Against such a loud and universal cry for relief, it seemed neither science nor religion, nor the Metropolitan Police, could explain the murderer, nor stop him.